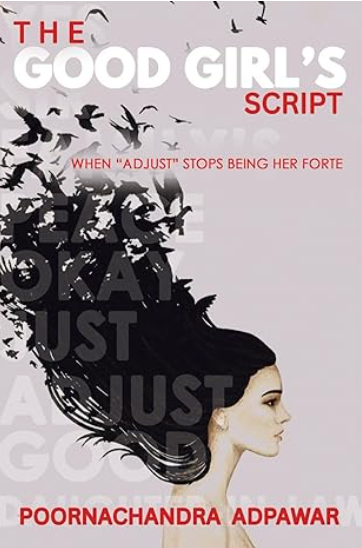

In a society where “adjust kar lo” echoes louder than a woman’s own voice, The Good Girl’s Script: When “Adjust” Stops Being Her Forte arrives like a mirror uncomfortable, necessary, and deeply human.

Through Anika’s journey, author Poornachandra invites readers to question the silent sacrifices women make: dreams folded away, ambitions dimmed, identities softened to preserve “ghar ka mahol.”

But this book isn’t just storytelling. It is a conversation, a rebellion, and at times, a hand gently placed on your shoulder saying, “You don’t have to be the good girl anymore.”

Today, we sit down with the author for a candid conversation about the book, the women who shaped him, and the script he hopes we all learn to rewrite.

Q1. Your writing often feels like a conversation over chai-warm yet deeply probing. What personal moment or realization first sparked The Good Girl’s Script?

Ans: Funny how writing works. I had a whole other topic in mind when I started. But then this title drifted in softly, almost shyly and before I knew it, it had taken over. I didn’t resist. I just followed.

“It’s fascinating how the stories that need to be told often find us, not the other way around. Almost like this book chose you.”

Q2. The phrase “adjust kar lo” runs like a refrain through your book. When did you first start questioning that script in your own life?

Ans: When a girl is born, a silent rule follows her: she must always oblige. I didn’t notice it at first. But as I grew up, I saw it everywhere in families, schools, cultures. It’s mostly women who are expected to adjust, to give in, to carry the burden. This pattern exists almost everywhere in the world.

“What surprises many is how quietly it gets written into a girl’s life before she even learns to speak.”

Q3. Anika’s story mirrors the emotional realities of so many women. How did you balance empathy with honesty while writing from a female perspective?

Ans: I never wrote for women. I wrote with them. Every time I sat down to type, three women were sitting right next to me: my mother, my sisters, my female friends. There’s a line in Chapter 9:

“This flat belongs to me too.” When I even thought about those words, my heart raced so hard I thought everyone could hear it. Make the reader feel that heartbeat.

So how did I balance empathy and honesty?

I never pretended to know their pain. I just refused to look away from it. I wasn’t the voice. I was the microphone.

“A powerful reminder of what true allyship looks like.”

Q4. You describe yourself as a “philosopher-punk” a rare mix! How does that duality shape your storytelling and your outlook on gender, freedom, and conformity?

Ans: Every chapter ends with a pause:

Philosopher’s pause – “Think.”

Punk punch – “Now DO.”

On gender, freedom, conformity?

I’m a guy, but when Maa’s gossip-book, series of complaints opens, I become her daughter for those five minutes. When my sister’s rishta meetings crush her laugh, I become the rebel brother who wants to set the marriage hall on fire (metaphorically, chill). I fight the system from the inside—that’s the punk move.

And I keep telling every woman who reads this:

You can be philosopher-punk too.

First Think.

Then Break something.

“A storyteller who tells us to think and break patterns That’s a combination literature needs more often.”

Q5. The Good Girl’s Script includes reflection prompts and letters to readers. Why was it important for you to blend storytelling with self-help elements?

Ans: Because I’ve seen what happens when a story ends and the reader closes the book…

and nothing changes. I didn’t want The Good Girl’s Script to be another “feel-good-then-forget” moment. Because a book that only makes you cry is entertainment.

A book that makes you change the Wi-Fi password so your husband finally learns to load the washing machine?

That’s revolution.

So yes I blended them because I’m done watching the women I love finish a story and still live the wrong one.

“Change the Wi-Fi password so he learns to use the washing machine” honestly, this is the kind of humour that hits with truth.”

Q6. Your Maa and sisters seem to be the heartbeat of your work. How have their experiences shaped your understanding of strength and silence?

Ans: They are the reason I am who I am today. From my earliest memories, they were there gently correcting me, guiding me, shaping my understanding of the world. They taught me how to behave, not just in public, but within the quiet walls of home, where expectations often speak louder than words. And most of all, I was taught that I must learn every household chore my sisters did not because I was expected to help, but because I was expected to know.

Looking back, I see both care and conditioning in those moments. They wanted me to be capable, prepared, accepted. But in doing so, they also handed me a script one that many girls across the world are given, often without realizing it.

“Your honesty about care and conditioning makes this answer stand out it’s the duality many families rarely acknowledge aloud.”

Q7. In today’s India, conversations around “saying no” are growing louder. What kind of dialogue do you hope your book sparks among men and women?

Ans: I want men to stop saying “ghar ka mahol” as an excuse.

I want women to stop saying “theek hain” as a reflex. That’s the revolution I’m greedy for.

Not loud. Just normal.

So, if one couple, one family, one dinner table at a time…

We replace “just adjust” with “let’s share”.

I’ll consider this book a bestseller in the only currency that matters- real homes, real voices, real freedom.

“A quiet revolution that begins at the dining table what a beautiful way to imagine change.”

Q8. If Anika could speak directly to your readers today, what would she say?

Ans: If Anika walked out of the book right now, sat on your bed, and looked you straight in the eye, this is what she’d say:

“Hey, listen…

I know you’re tired.

I know you just said ‘theek hai’ to the tenth thing today that you didn’t want to do.

I know your heart is racing because you’re scared that if you stop adjusting, everything will fall apart.

But here’s the truth I learned the hard way:

Nothing falls apart when you stop carrying everyone.

Everything falls into place when you finally carry yourself.

Your flat is yours too.

Your time is yours too.

Your dreams are yours too.

Stop waiting for permission.

Stop waiting for the ‘right time’.

Stop waiting for them to notice you’re drowning.

Tonight, do one tiny thing just for you.

One run.

One page in your dusty diary.

One ‘no’ whispered under your breath.

Because the day you stop saying sorry for existing…

is the day you start existing.

And trust me,

the world doesn’t end.

It just becomes a little more yours.

Now go.

I’m waiting in Chapter 10 to high-five you when you get there.

– Anika

“This answer feels like a chapter by itself. You’ve given Anika a voice that many real women might borrow until they find their own.”

Q9. How was your publishing experience? If you were to give advice to aspiring authors, what would it be?

Ans: I would say that my experience with Paper Towns was amazing. Right from Day 1, each and every doubt of mine, my concern about my budget constraint and what not was very well handled by Krati. When in the production phase, my manager Palak was there with me throughout the day following up with me and resolving my queries more like a friend. And last but not the least, I would like to thank Vidhisha who was patient while designing the book cover which is intricate in its design, symbolic in its imagery, and offers a subtle narrative hint that draws the reader into the story before the first page is turned.

“It’s refreshing to hear genuine gratitude in an industry often filled with anxiety and uncertainty.”

Q10. Finally, what’s next for you as a poet, as a storyteller, and as a man rewriting scripts?

Ans: I do have some plans for the coming year. Maybe it will be a new short story breaking one more cliche, a narrative poetry, or may be a fully-fledged novel on some common unaddressed issue. Can’t say…

“Sounds like the next story is already knocking you just haven’t opened the door yet.”

The Good Girl’s Script is not just a book; it’s a pause, a breath, and sometimes, a push.

Through Anika’s journey and the author’s unapologetically honest voice, readers are reminded that silence is not virtue, and “adjusting” is not a life skill it’s a slow erasure.

This interview leaves us with a quiet but powerful question:

If women have adjusted for generations, isn’t it time the world adjusts for them just once?

Whether you’re someone who has lived Anika’s story or someone who has unknowingly contributed to it, this book invites you to reflect, unlearn, and rewrite.

Because the day “adjust” stops being your forte…

is the day your real script begins